Operations leadership often considers equipment maintenance to be a cost center. But if a manufacturing plant executes maintenance effectively, the site will achieve better productivity, costs, safety, and staff retention.

The reality is that manufacturing leaders can get stuck in a break-fix model. Recent research found that 57% of facilities default to run-to-failure programs. They’re too busy fighting fires to uncover ways to fireproof the building. However, taking the time to assess, implement, and improve maintenance programs can yield powerful benefits. Consider that unplanned downtime costs an average of 11% of revenue at the world’s largest companies. Aging equipment and mechanical failure are the leading causes of downtime. Proactive, data-driven strategies minimize downtime, maximize asset performance, and reduce the cost of parts, equipment, and overtime.

Assess Your Maintenance Maturity

A structured assessment helps organizations understand their practices across every dimension of maintenance management. Once you understand the organization’s strengths and weaknesses, you can identify opportunities for improvement. You can view the assessment as a scorecard and use it as strategic tool to drive ongoing conversations and make decisions.

Understanding a quantifiable baseline across multiple dimensions lets you prioritize initiatives based on data rather than intuition. It also helps ensure resources—both people and dollars—are allocated where they will have the most impact. And you can invest more wisely in training and technology, which in turn supports better scheduling, reporting, and risk mitigation.

A structured approach to maintenance also helps to foster alignment across departments. Clearly defining roles, responsibilities, and expectations allows teams to work more cohesively, which is crucial for sustaining improvements and embedding a culture of continuous improvement.

Organizations can set realistic goals, track progress, and celebrate milestones. Each step forward contributes to a more resilient and efficient operation.

10 Dimensions of the Maintenance Model

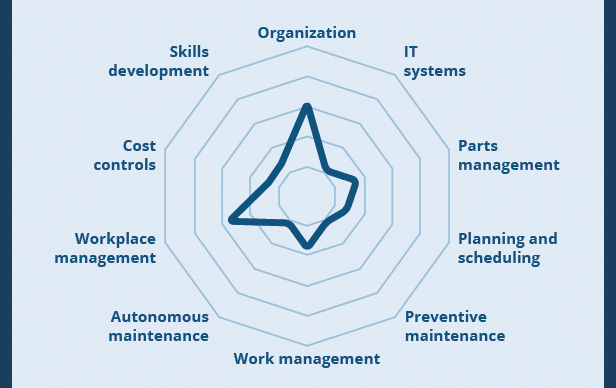

Based on working with multiple manufacturers over the years, Integrated Project Management Company (IPM) recommends that you assess and strengthen 10 key components. These include traditional themes you’d find in Society for Maintenance & Reliability Professionals (SMRP) and Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) models. They also include digital integration dimensions. The intention is to reflect a holistic view of maintenance as both a business system and a shop-floor practice.

- Organization: There are enough staff who can effectively execute equipment maintenance, and their roles and responsibilities are defined.

- IT systems: Digital tools hold information on equipment and parts, help schedule work and resources, and support maintenance management and reporting. These tools run the gamut from spreadsheets to integrated enterprise asset management (EAM), computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS), and enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems with predictive analytics.

- Parts management: Parts requirements for critical equipment are identified, you have the parts and consumables needed for equipment maintenance, and they’re managed cost effectively.

- Planning and scheduling: You have master plans and weekly and daily schedules for preventive maintenance activities.

- Preventive maintenance: There are equipment maintenance requirements and plans for critical equipment. Condition monitoring systems and reliability analysis methods enable predictive maintenance.

- Work management: You convert equipment maintenance requirements into work orders, then track each to closure. There are processes to monitor quality and manage and minimize work-order backlogs.

- Autonomous maintenance: Operations personnel understand their responsibility and standards for equipment care and have the skills to do it. This may include detecting and reporting problems.

- Workplace management: Work areas are clean and organized; tools and materials are close and easily accessible; and signs or charts inform staff of status or needs.

- Cost controls: You record maintenance costs for each work order and track costs for each asset as well as consumables. And you identify and act on budget variances.

- Skills development: Critical skills have been identified, training and coaching are in place, and maintenance staff have achieved those skills.

IPM rates each dimension on a 5-point scale: inconsistent, basic, competent, advanced, best in class. Then the results are mapped on a spiderweb or radar chart to easily visualize strengths, weaknesses, and imbalances. (Download the PDF for a Maintenance Maturity Self-Assessment worksheet.)

How to Use the Model to Improve Maintenance Maturity

First, it may be helpful to refine the dimensions to match your organization’s strategy, language, and culture. When people look at the chart, they should understand it readily, without having to learn new terms or concepts.

Position it as a decision-making tool rather than just a scorecard or audit. It’s human nature to become defensive when results sound like criticism. Instead, you might ask for validation: Is this where we are? What makes us advanced in this area? Where do we want to go?

Similarly, don’t be tempted to aim for world-class ratings on every element, at least not at once. Trying to improve on more than two or three dimensions would lead to fatigue. Start with improvements that will have the greatest impact by reducing costs and advancing the strategy.

For example, if many areas are level 1, or inconsistent, you might work toward stabilization and start with ensuring all dimensions are at least level 2. If you’re focused on reliability, you might prioritize preventive maintenance (perhaps by implementing condition monitoring systems) and work management (by converting routine maintenance into work orders and tracking completion). A highly automated site might put more weight on IT systems (invest in or optimize a computerized maintenance management system). A labor-intensive site might focus first on skills development and autonomous maintenance.

Finally, celebrate successes, but don’t update the model constantly. Revisiting it once or twice a year will ensure it’s visible and you can show progress. Refreshing it more often may turn it into a chore, and the fundamental elements are more likely to get lost.

Maintenance Improvement Case Examples

IPM’s manufacturing consultants have led maintenance improvement initiatives for several consumer and industrial products companies. Here are a handful of their recent successes.

Several Ounces of Prevention

When a food and beverage company bought a plant, it was able to retrofit some existing equipment and move some equipment from other facilities. The company had unmet demand, so they wanted to get up to speed quickly. They engaged IPM to document the assets and their associated preventive maintenance tasks (PMs), spare parts, and material costs. IPM identified all the pieces, old and new, and dug up materials and records wherever they could find them. The team provided all the necessary data to upload to the CMMS. Importantly, IPM pointed out critical risk areas, such as a conveyor that has a history of being unreliable and ages quickly, and recommended what to watch for to prevent problems. When the plant is fully functional, IPM will return to make sure the CMMS matches what actually happens.

Stay Up to Date

IPM worked with a food and beverage manufacturer that implemented a CMMS 10 years ago. Since then, the plant replaced assets and installed new lines, but they didn’t update the system. Over time, they moved more and more toward reactive maintenance. Downtime increased and production decreased. Collaborating with the maintenance leads, IPM identified the equipment, analyzed the manuals, and wrote descriptive preventive maintenance procedures. Crucially, the IPM consultant developed standard operating procedures for updating the CMMS when assets are added or removed, including who is responsible. This work will provide more line hours for the plant to run critical lines.

A Place for Everything and Everything in its Place

As part of a large operations improvement project with an industrial products company, IPM assessed the maintenance program. The consultant learned that there were $2.5 million worth of spare parts and assets that they couldn’t find. The parts were received and signed for, but not tracked. Were they used? Shipped to a different location? IPM worked with the facilities to find the parts and revise the digital and physical parts inventory system. This improvement will prevent the site from wasting technical resources’ time looking for lost parts, as well as prevent ordering additional parts due to poor organization.

Staffing Up to Drive Costs Down

The small maintenance team at an industrial plant was working overtime and constantly in break-fix mode. Labor costs and downtime were eating into margins. IPM recommended that they hire a clerk to handle inventory, parts, and small cleaning tasks. This would enable the highly qualified maintenance crew to focus on preventive maintenance and increase wrench time. Despite the additional headcount, the conservative savings estimate was $112,000, due to less overtime and downtime, and the ability to complete more preventive maintenance to improve equipment up time.

In Stock, No Waiting

An industrial products manufacturer expanded its facility and, as a preventive measure, asked IPM to identify failure points in the new line. Consultants walked the floor to document potential problems and prioritized four areas to focus on. They collected manuals, drawings, and bills of materials to identify the critical parts that the plant should keep in stock. In the past, it often had to wait weeks for delivery from overseas. With the critical parts on hand—and quantities up to date in the SAP—the facility will reduce downtime.

Visit Finding Pockets of Opportunity in Manufacturing Maintenance Protocols for a detailed case study about how a large food and beverage manufacturer used the maintenance assessment to define a roadmap toward almost $500,000 in annualized savings.

"*" indicates required fields