Solving the Resource Constraints Quandary

Nothing destroys an organization’s ability to execute more than resource constraints. Your organization has more work than its employees can handle, and “everything is important.” Executives say with pride, “We figure out a way to get it all done.”

There are a handful of reasons why project prioritization efforts fail, preventing an organization from accomplishing its most important initiatives. The problem may be lack of alignment between corporate and departmental priorities, or failure to communicate prioritization decisions or changes in priorities through the entire organization. Sometimes the prioritization methodology itself is the issue: people are able to game the system by inflating project benefits to justify their project’s importance; or the prioritization method is too complicated, so leaders don’t understand it, get frustrated, and ultimately push their projects through the organization based on their legacy knowledge and experience.

However, the primary reason that organizations fail to execute their prioritized projects is poor human resource management. Enterprise or functional leaders often make prioritization decisions without considering or understanding all the resource requirements. If the demand for resource support is greater than the resource availability (especially considering their functional responsibilities), projects either won’t get done or they will take much longer to complete. The latter can have a significant opportunity cost. Additionally, forcing extended work hours for a long period will likely lead to frustration, mistakes, turnover, and a deterioration in cultural positivity. Having a reasonably accurate estimate of supply and demand provides data to make informed staffing decisions such as hiring more resources, shifting specific resources from lower to higher priority initiatives, enlisting temporary support for day-to-day work or projects, or delaying projects until resources are available.

If project resources are overtaxed or not allocated properly, strategic goals will suffer. Organizations that assign qualified resources to plan and execute their most critical initiatives will undoubtedly realize a competitive advantage (assuming the strategy is effective).

What follows is a resource management framework to help measure supply and demand, identify constraints, and provide a reliable way to diminish resource dilution and increase the likelihood of realizing the most important initiatives. We offer recommendations for how to design the right resource management model and then put it to use within the portfolio management process.

Keep It Simple

Keep It Simple

When designing and implementing a resource management model, it should not be complex or difficult. It should be designed to make planning more effective and efficient. So keep it simple.

Track only the relevant data

With the enthusiasm around “big data,” some people have become overzealous about measuring everything. They implement expensive planning and time-tracking systems to collect data down to a tenth of an hour for every possible employee activity, then expect it to provide all the answers. The key is to collect enough resource data to paint a credible and ongoing picture of resource requirements to enable leaders to make project allocation decisions.

Augment data with a lot of discussion

Software will enable data collection and generate reports in a lot of detail. But the tool will only provide directional information in the beginning. Study the data in aggregate, use it to find constraints, and then go talk to the functional managers to validate accuracy and better understand the root causes of constraints. This is just the beginning; in each step of the resource management process, discussions are necessary to generate insight and solutions.

Only start projects that can be properly resourced.

If the data indicates there are insufficient resources and the functional managers confirm it, and the project is initiated anyway, there is a risk of failure. Most likely, if the project is completed, it took longer and/or something else has suffered. Realize, in this scenario, the process was compromised. It won’t take long for the organization to delegitimize the value of providing project resource estimates or tracking time accurately, since the data is not used for decision making. It is worthwhile for portfolio managers to establish an “in queue” or “parking lot” for projects requiring prioritization or awaiting resources.

Setting the Foundation

Setting the Foundation

There has to be a foundation upon which the resource management can stand. Without a well-functioning governance structure and established processes for project intake, evaluation, justification, prioritization, and maintenance—all focused on the well-defined objectives of the portfolio—it will be difficult for any resource management process to succeed. There will be no controls to start, defer, or reject projects, preventing an accurate picture of resource requirements. So focus first on the foundation.

If you are a functional leader without decision-making authority over the portfolio, you would still benefit from implementing a resource management process within your area of responsibility. Not only would it provide an assessment of the team’s capacity, allowing you to make informed decisions and provide guidance, but it would also provide data to evaluate and address new project support requests.

Take inventory

Once the portfolio management foundation is set, take an inventory of the current projects within the portfolio. It is critical that these projects have a direct contribution and measurable impact on the strategic goals and objectives of the portfolio; if they do not, they may be integrated into departmental objectives and should be considered part of the operational demand analysis.

Define reasonable and customary organizational work hour expectations

Define what a baseline work week means within the organization—40 hours, perhaps—for a typical full-time employee. This will give a conservative estimate of the resource hours available to support demand for projects within the portfolio as well as operational work. In reality, different types of resources have different levels of capacity for project work, often exceeding the baseline work week by six or eight hours.

Define the resource planning model

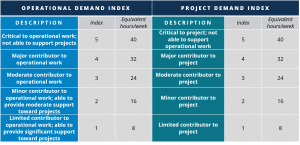

Before collecting resource data to measure operational and project demand, determine the right level of granularity. For example, one successful technique uses a scaled index to capture demand. A five-point scale breaks down the work week into 20 percent increments, as shown in Table 1: Resource Demand Index.

The right level of granularity is driven by how the resource planning model is designed, as detailed in the following section. After the model is designed, the “Putting the Model to Work” section will show how it’s used within the portfolio management process.

DESIGNING THE RIGHT RESOURCE PLANNING MODEL

DESIGNING THE RIGHT RESOURCE PLANNING MODEL

To design an appropriate resource planning model, the organization must dig more deeply into resource supply and demand to determine what level of information is necessary to make decisions. Understanding the key aspects of the portfolio is necessary to determining how complex the model needs to be. It requires answering questions such as, how often do projects get started, and how long do they typically last? How dynamic or static are the project resources throughout the project life cycle? How responsive does the business need to be to market factors?

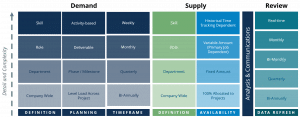

Consider the responses when designing the resource planning model. Follow these three steps: develop the parameters for presenting resource demand, define supply capacity, and establish a review cycle.

Step 1: Develop the parameters for resource demand

Establish the type of resources required to support the project portfolio. First determine the level of detail needed, as shown in Figure 1: Resource Planning Model Parameters. Most organizations evaluate resource needs by department or role, such as the nursing department or specifically RNs. In some cases, it is important to consider more granular level of requirements based on skill level, e.g., an IT developer with expertise in Android apps. In the interest of keeping it simple, use the broadest level that will identify potential constraints.

Next determine the parameters for how detailed project resource requests need to be. Consider the current resource planning competency of the organization. Requiring the most basic planning information, requests may be as simple as an IT resource for about four hours a week throughout the project. In a more sophisticated model, requests will include resource estimates by project phase or milestone. For instance, when developing a new product or service, they will need marketing and sales in the early stages to define the requirements and then not again until it’s time to prepare for market launch. In a mature organization, requests may identify necessary resources down to the deliverable or activity level using a detailed project plan. They may know that in weeks three and four, they need a laboratory assistant full time.

Finally, determine the timeframe, or incremental breakdown, for resource demand requests. Should requests outline the resources needed per month or quarter? Consider the usual length of projects and the organization’s ability to accurately predict project timelines.

Step 2: Define the supply capacity and capabilities

Once demand parameters have been established, determine the support requirement. Limit the focus to the key project resources. If project managers request resources at the role level, the available resources should be assigned at the role level.

Next, determine how precisely resource availability is calculated. The most basic method is by dedicating people—there are 12 individuals available to do project work. If people do project work on top of their day jobs, more detail is required. Estimate operational demand by role or person for a more accurate idea of time available for projects. Some organizations attempt to track actual time spent down to the hour or quarter hour; such historic data is more granular than most companies need to make resource allocation decisions.

Step 3: Establish a review cycle

The last step in designing a resource planning model is determining how often the data should be refreshed or updated. Dynamic, fast-moving project portfolios may require resourcing to be adjusted weekly. But for portfolios with longer projects, a quarterly review may be enough to monitor the status. Select the timeframe that is most appropriate for the organization’s project portfolio and ability to react as demands change. Establish processes and a communications platform for updating supply and demand.

Putting the Model to Work

Putting the Model to Work

Here’s how the resource planning model works within the project portfolio management process.

Gather and screen ideas

Managers and other leaders submit their project requests in a consistent format, providing information such as potential impact on the organization, broad estimates on duration and necessary resources, and alignment to the overall strategy. These ideas are screened to filter out the ones that aren’t aligned or have little value. Projects that are worthwhile but tactical are typically included in operational plans rather than the strategic portfolio.

Draft a charter

For the projects that pass the first screen, a charter is developed that more clearly defines the scope and business case and includes an estimate for demand of key resources.

Measure supply

On the agreed upon cadence, the project portfolio manager or process lead evaluates the resource pool. They determine how much resource supply remains after accounting for operational work and active projects.

Amend and adjust

The portfolio manager may request more detailed information about resources needed for new projects and potential adjustments the portfolio. Are there resource constraints that will prevent them from achieving their strategy? Are the most critical projects being worked on? Should an active project be put on hold until the needed resources are freed up? Portfolio management software will assist in running these analyses. It is advisable for the portfolio manager to meet with executives and managers to get their perspective and ensure they understand constraints and have an opportunity to address them.

Analyze the options

All the new project requests, as well as active projects and those in the “parking lot,” are compiled. The portfolio manager and/or governance committee prioritizes the new projects based on their predetermined criteria. (For a model that uses importance to the organization and complexity to guide prioritization, see sidebar “First Things First: Prioritization Criteria.”) They then evaluate the resource supply to determine if they have enough of the right people to do the work. It’s important to note that the supply parameters are often flexible; for example, resources who have full-time responsibilities can often support projects on top of their day jobs. It is not unusual for organizations to establish a 15 percent to 20 percent additional capacity (six to eight hours per week) for project work. However, when additional dedicated time is required to support a project, especially over an extended period, resource augmentation is required, or the project should be deferred.

Get to work

When the portfolio and resource allocation are approved, the new projects are activated, and people are assigned to project teams. A critical first step for each new project is to complete a detailed planning exercise, which may produce a more accurate estimate of the resource requirements. If this new estimate varies significantly (typically 10 percent or more) from the original, the project team should inform the portfolio manager, who must determine alternatives.

Maintain the portfolio

As part of the portfolio management process, the manager needs to routinely assess performance to ensure projects are likely to deliver to expectations. The cadence of reporting will vary, but a good place to start is quarterly.

Worth the Effort

Worth the Effort

Resource management is difficult because it depends on many variables that are constantly changing. However, when an organization commits to developing and maintaining a process within its project portfolio management structure, workload estimates and decisions will improve, and the most important projects will get done.

Keep It Simple

Keep It Simple Setting the Foundation

Setting the Foundation DESIGNING THE RIGHT RESOURCE PLANNING MODEL

DESIGNING THE RIGHT RESOURCE PLANNING MODEL Putting the Model to Work

Putting the Model to Work Worth the Effort

Worth the Effort